last modified: Wednesday, 30-Nov-2016 22:17:26 CET

Quartz crystals occur in a great number of different shapes. Most rockhounds are familiar with their look and immediately recognize quartz crystals, so despite the great number of varieties and growth forms, all quartz crystals share some characteristics.

This chapter briefly introduces quartz crystal morphology and the basic terms used to describe crystals. If you want to know more about quartz crystals you should continue with the chapters listed under "Next Chapters" which are also accessible via the menu to the right.

|

|

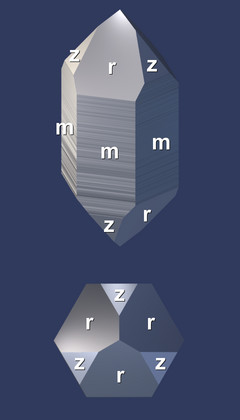

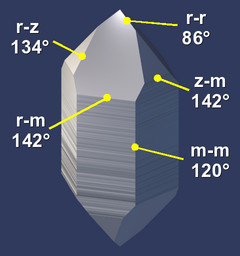

m: six faces belonging to the central six-sided prism with a typical horizontal striation

r: three, often roughly triangular faces at the crystal's tips. In well-developed crystals these faces are always present.

z: three, often triangular faces also at the crystal's tips, that sit between the r faces.

The basic shapes of most quartz crystals can be explained as variations of the relative sizes of these faces. The r faces are usually larger than the z faces, and are commonly presented that way in figures shown in mineralogy textbooks, but the size of each face depends much on the overall shape of the crystal, the growth conditions and the presence of other faces.

The top view shows that although the prism of the crystal is six-sided, it has a three-fold rotational symmetry. Quartz thus belongs to the trigonal crystal class.

|

|

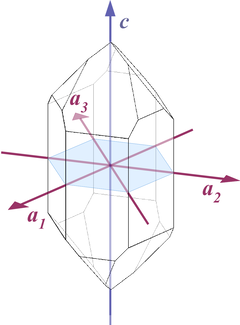

This would work for quartz crystals as well, but for practical reasons and because of symmetry considerations, in quartz 4 axes defined in the hexagonal crystal system are used and labeled a1, a2, a3, and c (Fig. 4). The 3 a-axes intersect at an angle of 60° and lie on a plane (Fig. 4, light blue), and the c-axis runs perpendicular to the plane and intersects all a-axes at an angle of 90°. Often there is no need to distinguish between a1, a2 and a3 and one simply refers to the a-axis or a0-axis.

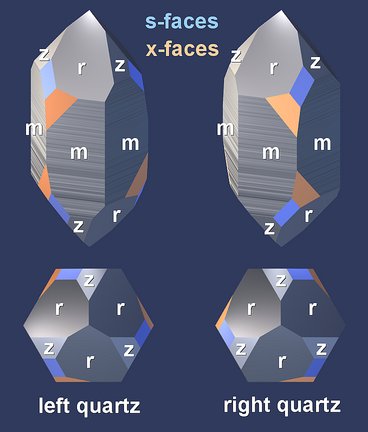

Quartz crystals lack mirror symmetry. The mirror image of a quartz crystal is different from the original image, no matter where the mirror plane lies.

Instead, quartz crystals show handedness: there are 2 types of crystals, left-handed and right-handed crystals. This is very similar to the human hand - you have a left and right hand. Each of them is a mirror image of the other, but the mirror image of the left hand is not a left hand, so each hand itself lacks internal mirror symmetry (unlike the human face, for example, which is roughly mirror symmetric).

|

The handedness of quartz is only visible on quartz crystals that possess certain crystal faces. Figure 5 is a rendering of a left-handed quartz crystal (there is a link to an MPEG4/H.264-movie of a rotating crystal below).

There is no inherent tendency in quartz to prefer one direction, and left- and right-handed quartz crystals occur at the same frequency.

The additional faces on Fig.5 are the s-faces and the x-faces. The typical s-face is a rhomb, whereas an x-face is usually either a triangle or - when it is bordering an s-face - a trapezoid.

The rule of thumb to determine the handedness is:

- If an x- or s-face is present at the left side of an r-face, the quartz is called left-handed (or left quartz, for short).

- If an x- or s-face is present at the right side of an r-face, the quartz is called right-handed (or right quartz, for short).

|

Left and right quartz are mirror images of each other, but lack mirror symmetry themselves.

Double-terminated crystals with all s- and x-faces on them like those on the idealized renderings are extremely rare. Most crystals don't show s- and x-faces, and those that do often have only one or two of them, and either x- or s-faces, but rarely both of them.

|

For example, in Fig.7 you see a rendering of a so-called Brazil twin, a crystal apparently formed by the superposition of a left- and a right-handed crystal. It is an apparent superposition because in fact different sections of the crystals are either left- or right-handed, and never both simultaneously.

Again, this is an idealized picture, and while natural crystals are twinned very often, they don't display the full range of crystal faces, making it difficult to recognize them. Brazil twins are common, but crystals that show a combination of faces like the one in the rendering are extremely rare.

Next Chapters

In the following chapters the various topics that have just been touched are discussed more thoroughly.Basic Terms briefly introduces a few basic crystallographic terms necessary to understand quartz crystal morphology.

Forms introduces the most common crystal faces in quartz and their underlying crystallographic forms.

Habits explains common terms used when describing the overall shape of crystals.

Twinning introduces the 3 types of twins that are found in quartz and explains how to identify them.

Data and Renderings explains how I did the computer renderings on these pages and offers a few data sets for download.

Further Information, Literature, Links

If you are not familiar with basic terms of crystallography, I'd strongly recommend not only to read the section Basic Terms but also to look at other sources in the Internet. Certain notions used when describing quartz crystals remain incomprehensible without a minimal background in crystallography. A very nice introduction by Mike and Darcy Howard can be found at this website at Bob's Rock Shop: Introduction to Crystallography and Mineral Crystal Systems. It is definitely worth a visit.Another page is discussing Crystals and Lattices, although the approach is rather mathematical.

Crystallographic terms can be quite confusing and I'd recommend to have a look at a good textbook of mineralogy to get more into it.

Printer Friendly Version

Printer Friendly VersionCopyright © 2005-2016, A.C. A k h a v a n

Impressum - Source: http://www.quartzpage.de/crs_intro.html